My First Repository

Introduction

-

The first two things you'll want to do is install

git, follow the instructions here to install git (if it's not already installed):-

In this tutorial, we'll be using Git exclusively from the command line. While there are many excellent Git GUIs (graphical user interfaces), it's generally easier to learn Git by starting with command-line tools. This helps build a solid understanding of how Git works under the hood.

-

Once you're comfortable with the basics and understand what's happening behind the scenes, you can explore a GUI. You'll be better equipped to troubleshoot issues and handle advanced tasks that some GUIs may not support as effectively.

-

-

Once you've done that, create a GitHub account using your university email address — not your Greenwich username. Be sure to choose a different password than the one you use for university systems:

-

-

When choosing a username, avoid using any personally identifiable information such as your full name, student ID, or email prefix. Pick something professional but anonymous.

-

Using your university email makes it easier to join the GRE GitHub organisation, https://github.com/UniOfGreenwich/, which uses SAML authentication for secure access.

Git and GitHub are not the same thing. Git is an open-source version control system created in 2005 by developers working on the Linux kernel. GitHub, on the other hand, is a company founded in 2008 that provides hosting and collaboration tools built around Git.

You don't need GitHub to use Git, but you do need Git to use GitHub. GitHub is just one of many platforms that support Git repositories. Other popular alternatives include GitLab, Bitbucket, and self-hosted solutions like Gogs and Gitea.

In Git terminology, these platforms are known as remotes—external locations where your code can be stored and shared. Using a remote is entirely optional, but it makes collaboration and sharing much easier.

-

-

Step 1: Create a local git repository

When creating a new project on your local machine using git, you'll first create a new repository (or often, 'repo', for short).

To use git we'll be using the terminal.

-

To begin, open up a terminal and move to where you want to place the project on your local machine using the cd (change directory) command. For example, if you have a 'projects' folder on your desktop, you'd do something like:

-

To initialize a git repository in the root of the folder, run the

git initcommand:hint: Using 'master' as the name for the initial branch. This default branch name hint: is subject to change. To configure the initial branch name to use in all hint: of your new repositories, which will suppress this warning, call: hint: hint: git config --global init.defaultBranch <name> hint: hint: Names commonly chosen instead of 'master' are 'main', 'trunk' and hint: 'development'. The just-created branch can be renamed via this command: hint: hint: git branch -m <name> Initialized empty Git repository in /home/seb/Documents/myfirstrepository/.git/ -

Regardless of the output above, rename the current branch with:

Step 2: Add a new file to the repo

-

Go ahead and add a new file to the project, using any text editor you like or running a touch command.

touch newfile.txtjust creates and saves a blank file namednewfile.txt. -

After creating the new file, you can use the

git statuscommand to see which filesgitknows exist.On branch main No commits yet Untracked files: (use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed) compeng0001.txt nothing added to commit but untracked files present (use "git add" to track)-

What this basically says is, "Hey, we noticed you created a new file called compeng0001.txt, but unless you use the

git addcommand we aren't going to do anything with it." -

Once you've added or modified files in a folder containing a

gitrepo,gitwill notice that the file exists inside the repo. But,gitwon't track the file unless you explicitly tell it to. Git only saves/manages changes to files that it tracks, so we’ll need to send a command to confirm that yes, we wantgitto track our new file.

-

One of the most confusing parts when you're first learning git is the concept of the staging environment and how it relates to a

commit. -

A commit is a record of what changes you have made since the last time you made a commit. Essentially, you make changes to your repo (for example, - ding a file or modifying one) and then tell git to put those changes into a

commit. -

Commits make up the essence of your project and allow you to jump to the state of a project at any other

commit. -

So, how do you tell git which files to put into a

commit? This is where the [staging environment](https://git-scm.com/book/en/v2/- t-Basics-Recording-Changes-to-the-Repository) or index come in. As seen in Step 2, when you make changes to your repo, git notices that a file has changed but won't do - ything with it (like adding it in a commit). -

To add a file to a commit, you first need to add it to the staging environment. To do this, you can use the

git add <filename]>- mmand (see Step 3 below). -

Once you've used the git add command to add all the files you want to the staging environment, you can then tell git to package them into a commit using the

git commitcommand. -

Note: The staging environment, also called 'staging', is the new preferred term for this, but you can also see it referred to as the 'index'.

-

Step 3: Add a file to the staging environment

-

Add a file to the staging environment using the

git addcommand. -

If you rerun the

git statuscommand, you'll see that git has added the file to the staging environment (notice the "Changes to be committed" line).On branch main No commits yet Changes to be committed: (use "git rm --cached <file>..." to unstage) new file: compeng0001.txt -

However, first we need to make sure we have some creditentials for the commit to log who and when.

-

First set your username:

-

Next set your email:

-

Example of the above:

-

Step 4: Create a commit

It's time to create your first commit!

-

Run the command

git commit -m "Your message about the commit"[main (root-commit) f2e1069] init: This is my first commit 1 file changed, 0 insertions(+), 0 deletions(-) create mode 100644 compeng0001.txtThe message at the end of the commit should be something related to what the commit contains - maybe it's a new feature, maybe it's a bug fix, maybe it's just fixing a typo. Don't put a message like "asdfadsf" or "foobar". That makes the other people who see your commit sad. Very, very, sad. Commits live forever in a repository (technically you can delete them if you really, really need to but it’s messy), so if you leave a clear explanation of your changes it can be extremely helpful for future programmers (perhaps future you!) who are trying to figure out why some change was made years later.

Step 5: Create a new branch

Now that you've made a new commit, let's try something a little more advanced.

Say you want to make a new feature but are worried about making changes to the main project while developing the feature. This is where git branches come in.

Branches allow you to move back and forth between 'states' of a project. Official git docs describe branches this way: ‘A branch in Git is simply a lightweight movable pointer to one of these commits.’ For instance, if you want to add a new page to your website you can create a new branch just for that page without affecting the main part of the project. Once you're done with the page, you can merge your changes from your branch into the primary branch. When you create a new branch, Git keeps track of which commit your branch 'branched' off of, so it knows the history behind all the files.

Let's say you are on the primary branch and want to create a new branch to develop your web page. Here's what you'll do: Run git checkout -b <my branch name>. This command will automatically create a new branch and then 'check you out' on it, meaning git will move you to that branch, off of the primary branch.

-

After running the above command, you can use the

git branchcommand to confirm that your branch was created:* dev main

- The branch name with the asterisk next to it indicates which branch you're on at that given time.

-

By default, every git repository’s first branch is named

master(and is typically used as the primary branch in the project). As part of the tech industry’s general anti-racism work, some groups have begun to use alternate names for the default branch (we are using “primary” in this tutorial, for example). In other documentation and discussions, you may see “master”, or other terms, used to refer to the primary branch. Regardless of the name, just keep in mind that nearly every repository has a primary branch that can be thought of as the official version of the repository. If it’s a website, then the primary branch is the version that users see. If it’s an application, then the primary branch is the version that users download. This isn’t technically necessary (git doesn’t treat any branches differently from other branches), but it’s how git is traditionally used in a project. -

If you are curious about the decision to use different default branch names, GitHub has an explanation of their change here: https://github.com/github/renaming

-

Now, if you switch back to the primary branch and make some more commits, your new branch won't see any of those changes until you

mergethose changes onto your new branch.

Step 6: Create a new repository on GitHub

If you only want to keep track of your code locally, you don't need to use GitHub. But if you want to work with a team, you can use GitHub to collaboratively modify the project's code.

-

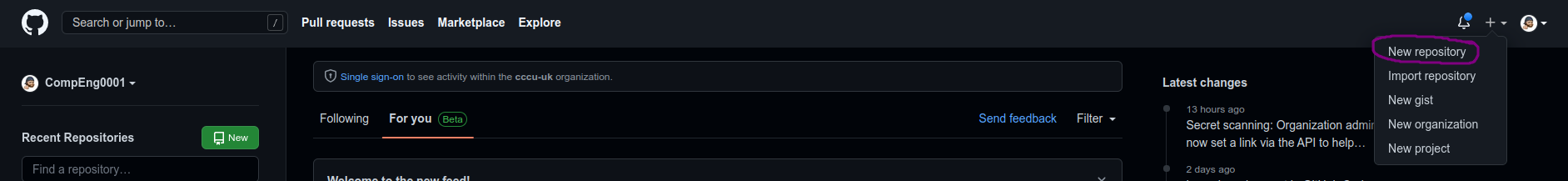

To create a new repo on GitHub, log in and go to the GitHub home page. You can find the “New repository” option under the “+” sign next to your profile picture, in the top right corner of the navbar:

-

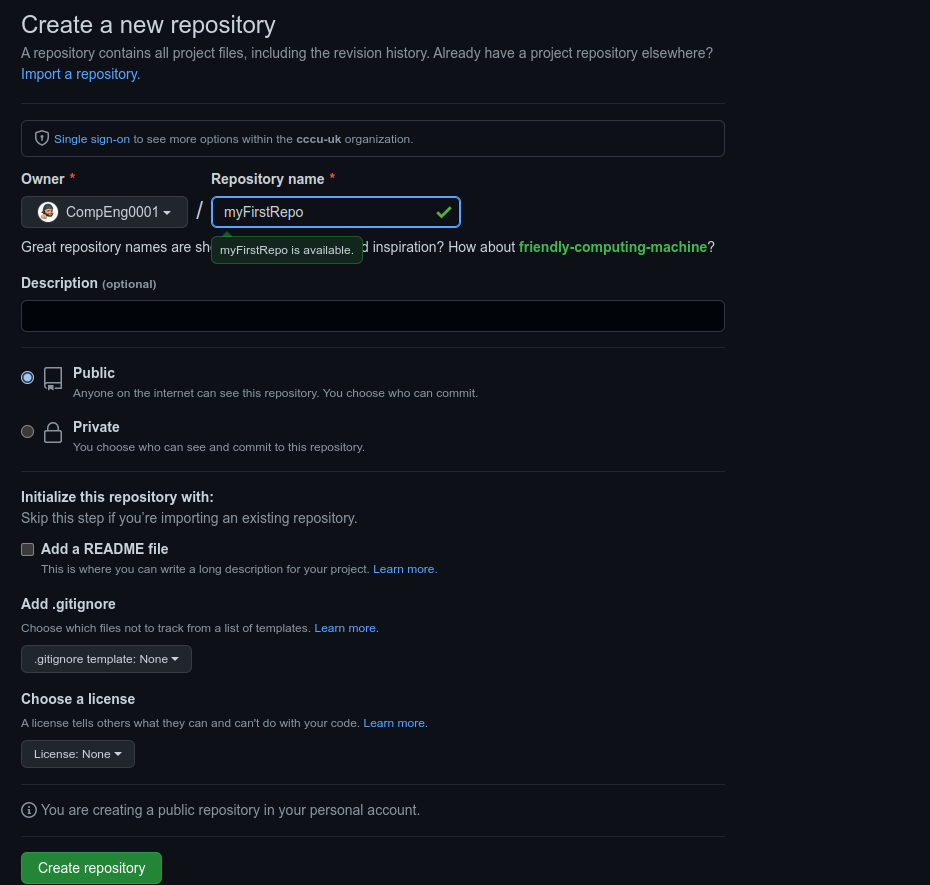

After clicking the button, GitHub will ask you to name your repo and provide a brief description:

-

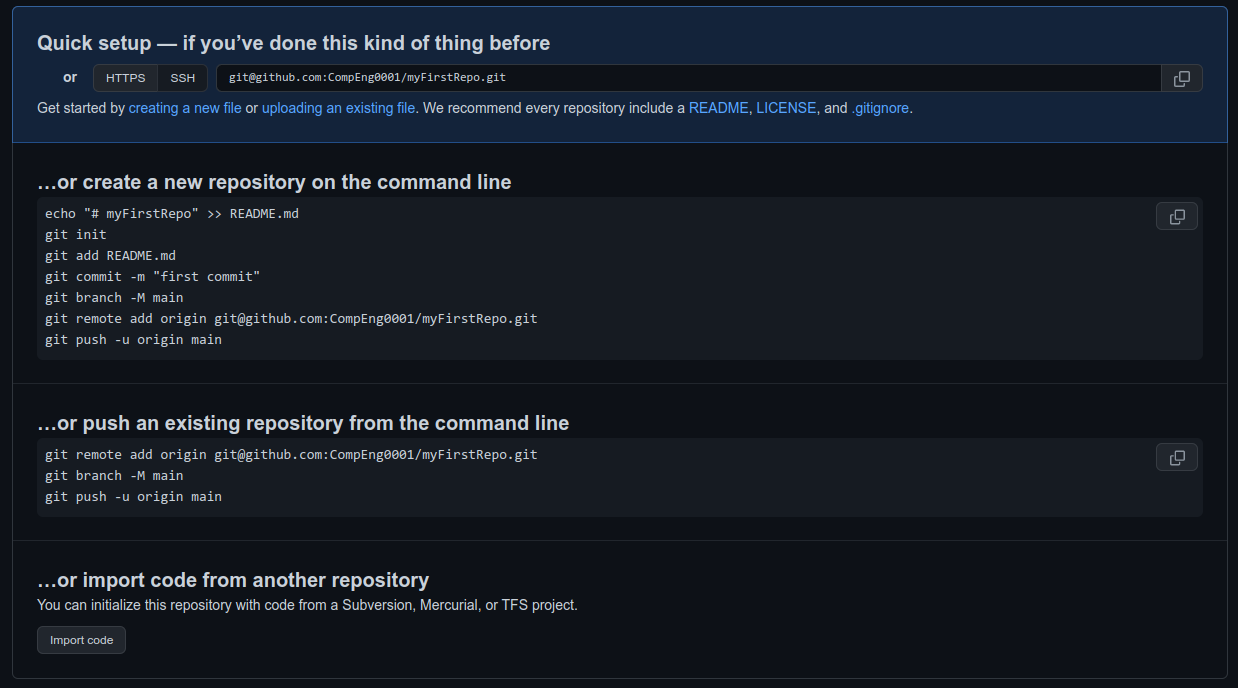

You will see your new repo has been created with some useful instructions on creating and pushing a repo.

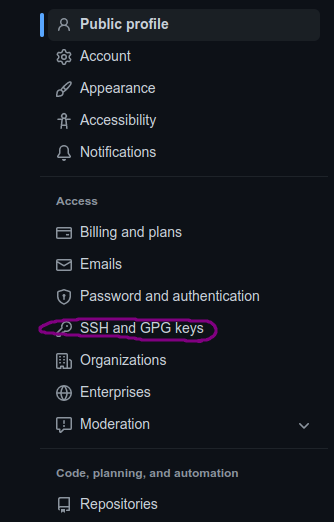

Security and authentication

You need to create an ssh key to push and pull to your online storage/repo before we try to sync with the cloud.

-

You need to make sure that you

~/.sshdirectory exists before you attempt to make an ssh key.If the output is below then the directory already existed, else it will show nothing and you will have created the directory

-

Now you need to get your public key you have generated and add to GitHub, go back to the terminal.

-

Press Enter until you get no more ouput.

-

You can review your newly created public key like this:

-

The copy the output from

ssh-ed25519 ... YourGitEmailto your clipboard and follow the screenshots below.

-

Once completed, go back to the terminal and lets check for a connection:

-

You may see a similar output below, ensure you write

yes...The authenticity of host 'github.com (140.82.121.4)' can't be established. ED25519 key fingerprint is SHA256:+DiY3wvvV6TuJJhbpZisF/zLDA0zPMSvHdkr4UvCOqU. This key is not known by any other names Are you sure you want to continue connecting (yes/no/[fingerprint])? yesWarning: Permanently added 'github.com' (ED25519) to the list of known hosts. PTY allocation request failed on channel 0 Hi CompEng0001! You've successfully authenticated, but GitHub does not provide shell access. Connection to github.com closed.

Step 7: Push a branch to GitHub

Now we'll push the commit in your branch to your new GitHub repo. This allows other people to see the changes you've made. If they're approved by the repository's owner, the changes can then be merged into the primary branch.

-

First create a reference to the online repo.

-

To push changes onto a new branch on GitHub, you'll want to run

git push origin yourbranchname. GitHub will automatically create the branch for you on the remote repository: -

Now go back to the main branch and lets make sure that is pushed to the cloud aswell.

-

...then:

Total 0 (delta 0), reused 0 (delta 0), pack-reused 0 remote: remote: Create a pull request for 'main' on GitHub by visiting: remote: https://github.com/CompEng0001/myFirstRepo/pull/new/main remote: To github.com:CompEng0001/myFirstRepo.git * [new branch] main -> main branch 'main' set up to track 'origin/main'.You might be wondering what that "origin" word means in the command above. What happens is that when you clone a remote repository to your local machine, git creates an alias for you. In nearly all cases this alias is called "origin." It's essentially shorthand for the remote repository's URL. So, to push your changes to the remote repository, you could've used either the command:

git push git@github.com:git/git.git yourbranchnameorgit push origin yourbranchname -

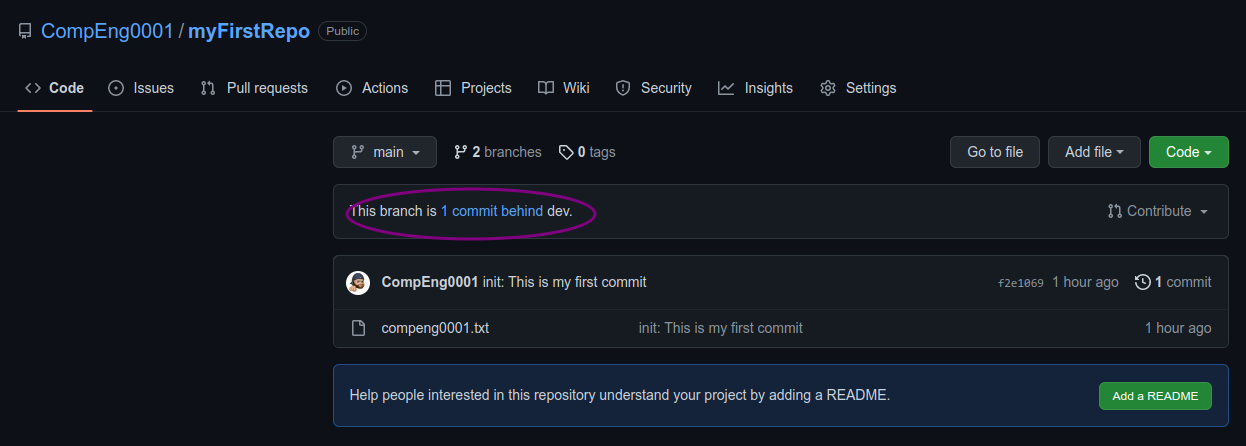

If you refresh the GitHub page, you'll see note saying a branch with your name has just been pushed into the repository. You can also click the 'branches' link to see your branch listed there.

-

Now lets make a change locally in the

devbranch.[dev 8285ba4] add: a new file added 1 file changed, 0 insertions(+), 0 deletions(-) create mode 100644 anewfile.txtfatal: The current branch dev has no upstream branch. To push the current branch and set the remote as upstream, use git push --set-upstream origin devEnumerating objects: 3, done. Counting objects: 100% (3/3), done. Delta compression using up to 4 threads Compressing objects: 100% (2/2), done. Writing objects: 100% (2/2), 264 bytes | 264.00 KiB/s, done. Total 2 (delta 0), reused 0 (delta 0), pack-reused 0 To github.com:CompEng0001/myFirstRepo.git f2e1069..8285ba4 dev -> dev branch 'dev' set up to track 'origin/dev'.

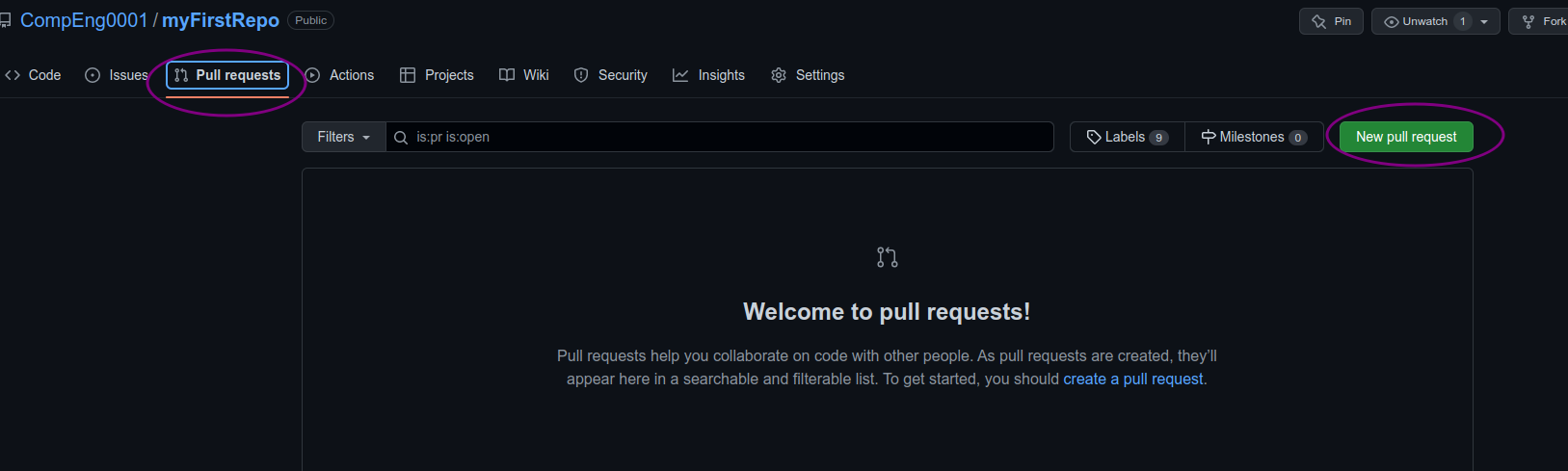

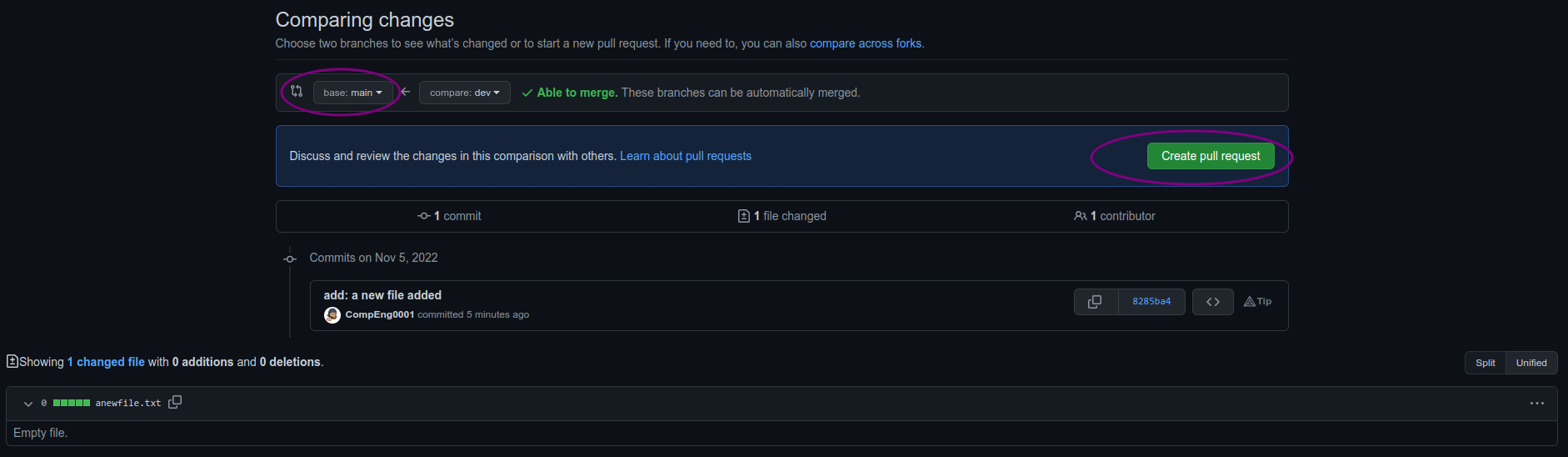

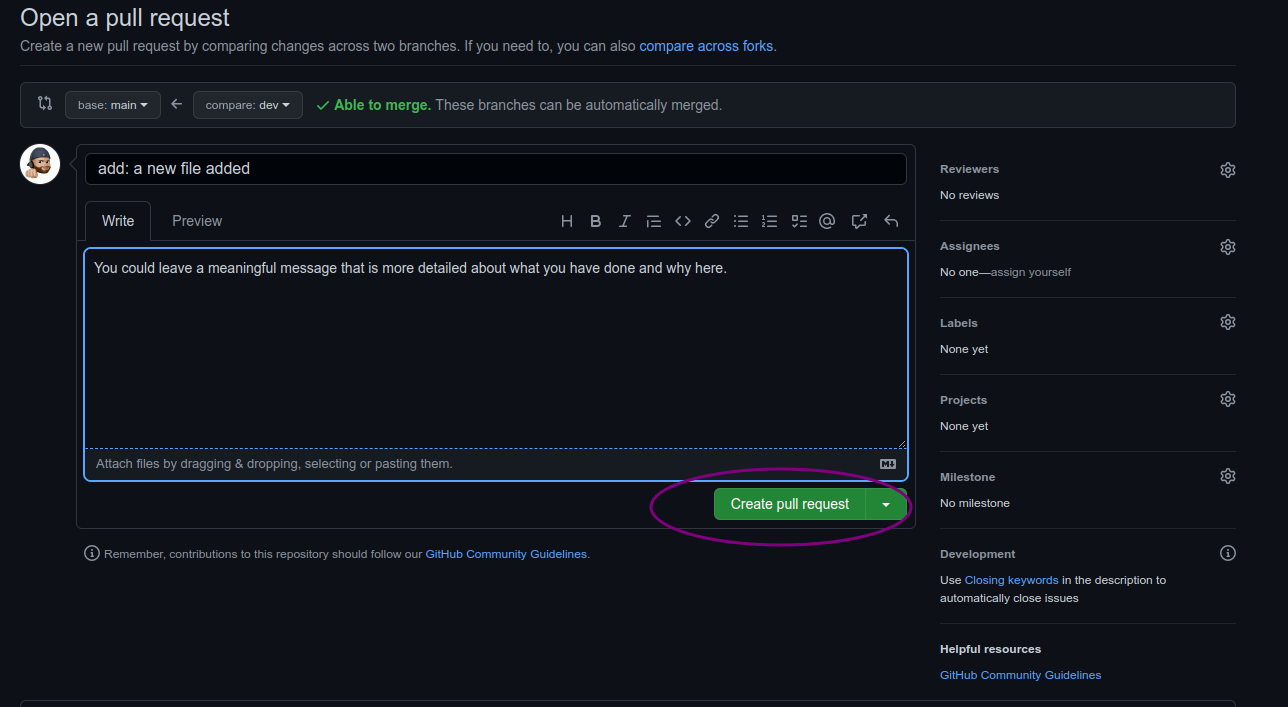

Step 8: Create a pull request (PR)

A pull request (or PR) is a way to alert a repo's owners that you want to make some changes to their code. It allows them to review the code and make sure it looks good before putting your changes on the primary branch.

-

This is what the PR page looks like before you've submitted it:

-

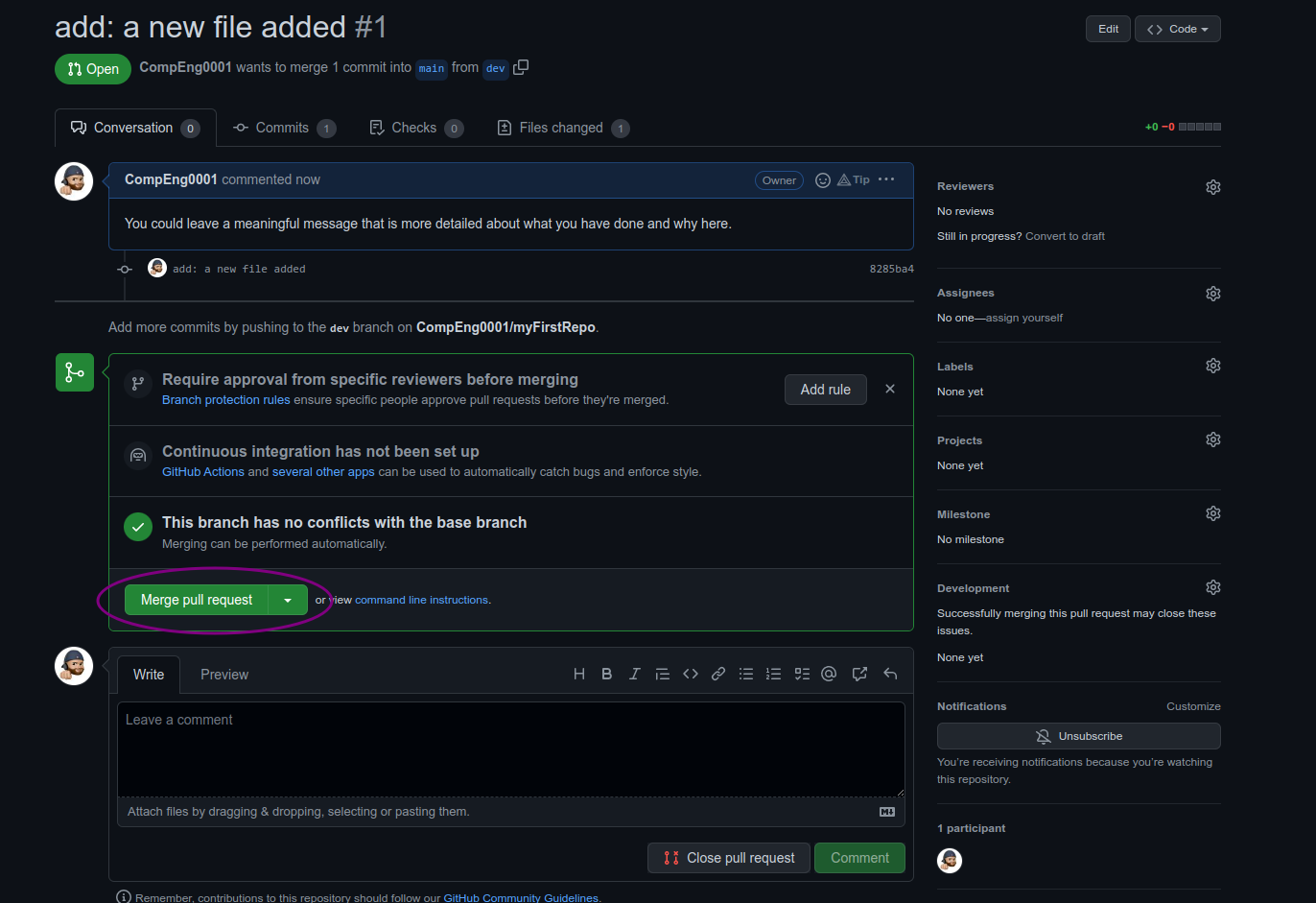

And this is what it looks like once you've submitted the PR request:

-

You might see a big green button at the bottom that says 'Merge pull request'. Clicking this means you'll merge your changes into the primary branch..

Sometimes you'll be a co-owner or the sole owner of a repo, in which case you may not need to create a PR to merge your changes. However, it's still a good idea to make one so you can keep a more complete history of your updates and to make sure you always create a new branch when making changes.

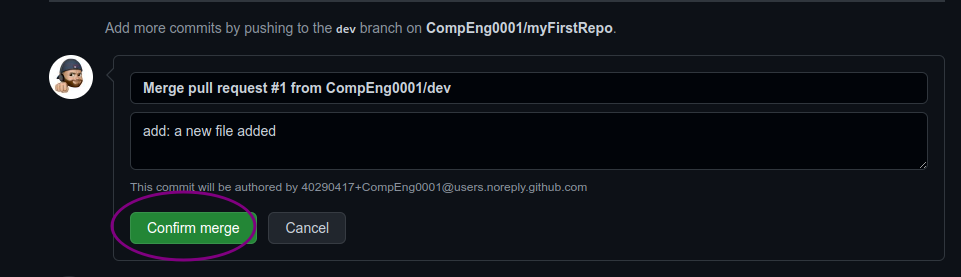

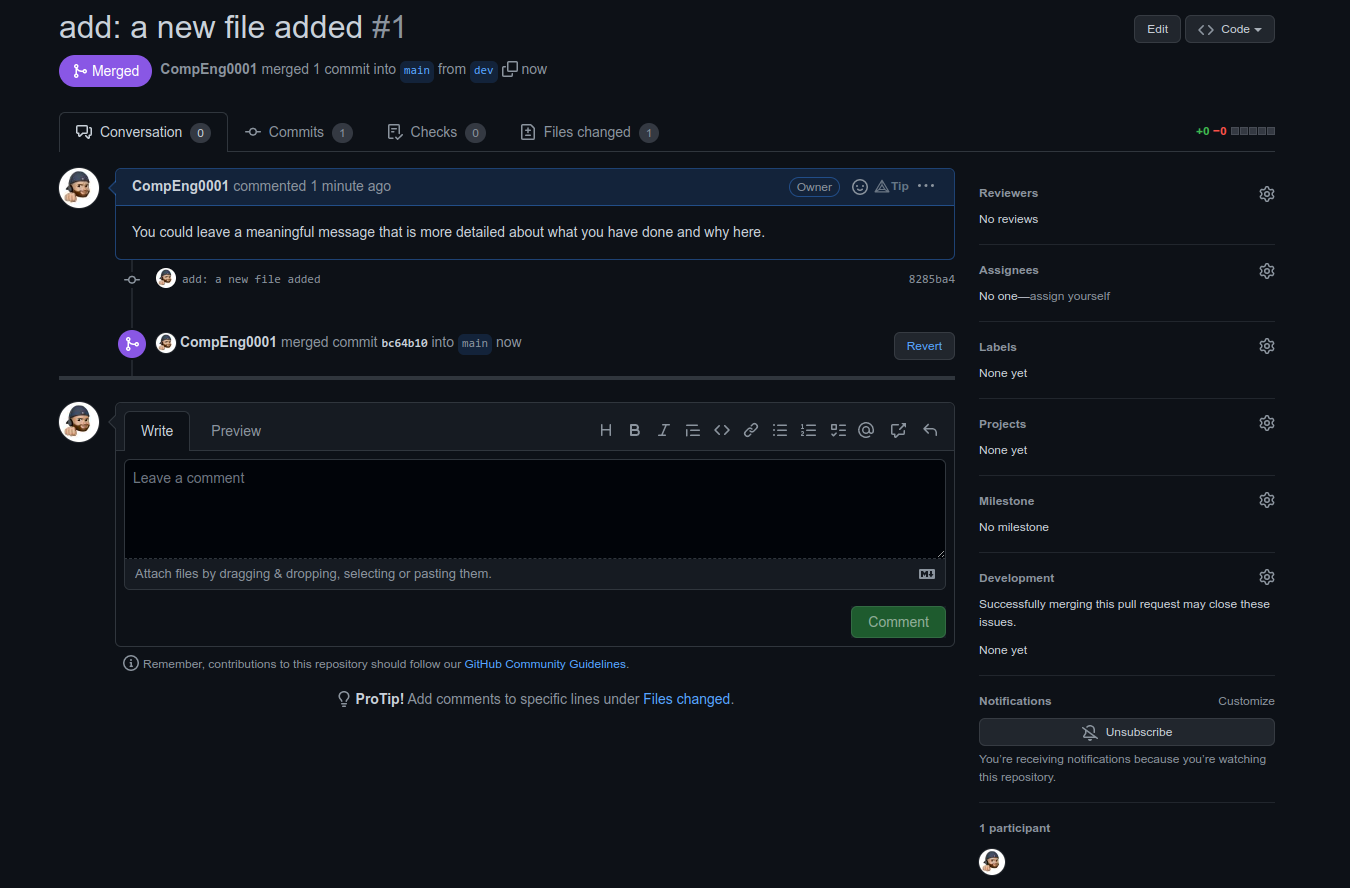

Step 9: Merge a PR

-

Go ahead and click the green 'Merge pull request' button. This will merge your changes into the primary branch.

-

You can double check that your commits were merged by clicking on the 'Commits' link on the first page of your new repo.

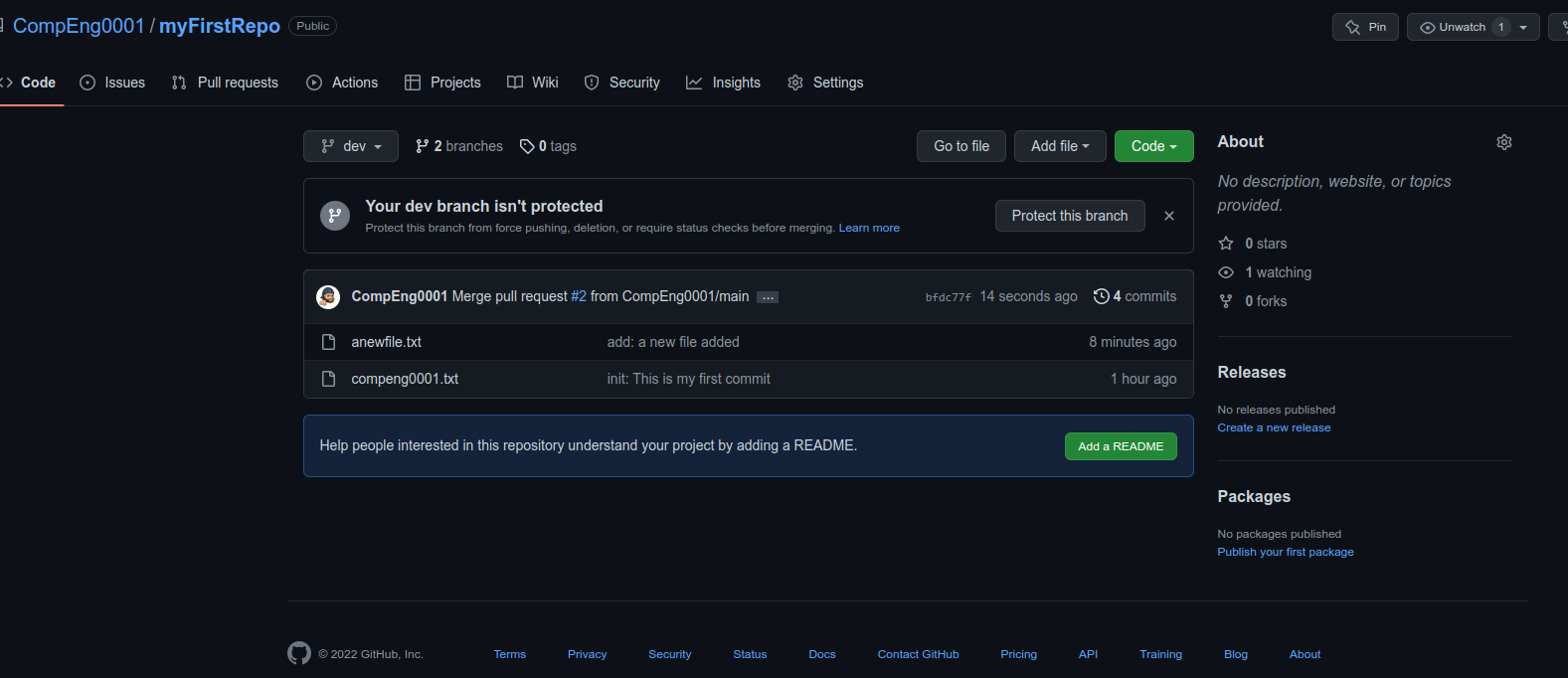

Step 10: Get changes on GitHub back to your computer

Right now, the repo on GitHub looks a little different than what you have on your local machine. For example, the commit you made in your branch and merged into the primary branch doesn't exist in the primary branch on your local machine.

-

In order to get the most recent changes that you or others have merged on GitHub, use the

git pull origin maincommand(when working on the primary branch). In most cases, this can be shortened togit pull.remote: Enumerating objects: 2, done. remote: Counting objects: 100% (2/2), done. remote: Compressing objects: 100% (2/2), done. Unpacking objects: 100% (2/2), 1.20 KiB | 1.21 MiB/s, done. remote: Total 2 (delta 0), reused 0 (delta 0), pack-reused 0 From github.com:CompEng0001/myFirstRepo f2e1069..bc64b10 main -> origin/main 8285ba4..bfdc77f dev -> origin/dev Updating f2e1069..bc64b10 Fast-forward anewfile.txt | 0 1 file changed, 0 insertions(+), 0 deletions(-) create mode 100644 anewfile.txt -

Now we can use the

git logcommand again to see all new commits.commit bc64b101b966bcee5f8b87c451b674450638d981 (HEAD -> main, origin/main) Merge: f2e1069 8285ba4 Author: CompEng0001 <40290417+CompEng0001@users.noreply.github.com> Date: Sat Nov 5 12:46:32 2022 +0000 Merge pull request #1 from CompEng0001/dev add: a new file added commit 8285ba429f3ab757e8549416b33dde454e563e09 (dev) Author: CompEng0001 <sb1501@canterbury.ac.uk> Date: Sat Nov 5 12:39:27 2022 +0000 add: a new file added commit f2e1069137b6bc0115e119b3aae83c35cc1d0358 Author: CompEng0001 <sb1501@canterbury.ac.uk> Date: Sat Nov 5 11:52:16 2022 +0000 init: This is my first commit -

Well done, you have completed the first git workflow!